After the successes and failures of making and baking our own versions of Barvas Ware, the rare ceramic vessels from the Island of Lewis, Helen and I moved on to working with a group of objects that were once far more commonplace.

The Highland Folk Museum’s collection of hornware, including spoons and tumblers.

Horn, taken from cows, oxen and rams, was once a material that could be found within almost every home within the Highlands in a variety of forms including spoons, scoops and tumblers. Horn is a form of keratin, just like human hair and nails, and unlike antlers which are shed and regrown each year, horn starts to grow soon after birth and develops throughout the life span of an animal. It grows in layers around a bony core which extends from the skull, and is known for being a natural thermoplastic, meaning that it may be easily shaped when heated. Given how readily available horn was within the Highlands, as well as how durable and how easy to clean it is, it is not surprising that the Highland Folk Museum has a large collection of hornware.

Above – KIGHF.PH.0005, a pair of horns from a Highland bull

Below – KIGHF.PH.0019, an unworked horn.

To remove a horn from the skull of an animal it must be either rotted or soaked in water for several months. Once removed the horn is then often cut lengthways and flattened between two flat plates of metal, forming sheets of material to work with. In some cases, such as in the windows of lanterns, the horn was used as a sheet, but more often it was further worked, such as in the creation of spoons.

Our knowledge of how horn was worked once removed from the skull is patchy, and especially in how it was transformed in to a spoon, as it was generally a skill undertaken by the Travellers. The Travellers led a nomadic lifestyle and would pitch their bow tents on the edge of villages, earning money as tinsmiths, horners and basket makers. I.F. Grant discusses in Highland Folk Ways how some of her visitors as boys were “sometimes told to take a cow’s horns to the tinkers to be made into spoons. The tinkers would tell them to go away and come back to collect the spoons. They were never allowed to see the process of manufacture, afraid that the carefully kept secret might have been discovered.” (1) Fortunately, within our collection we have a very unique spoon with a very special story, which gives an excellent insight in to how spoons were made.

Above: SKA.0105, Dugald’s spoon

Below: SKA.0058, a wooden spoon mould

This particular spoon was made on a doorstep in Tobermory for the 7th birthday of the Very Reverend Dugald Macfarlane, and was commissioned from a traveller by Dugald’s mother in 1877. Dougald, as an old man, recounted how the spoon was made:

“He [the Traveller] cut the horn in three stripes. A medium dark horn. Then boiled it in Mrs Macdougall’s hens pot then beat it and flexed it then put it into his spare mould of wood with one half a bump and the other a hollow and jointed with a leather thong. Then it was lashed down at the free end and the horn trimmed with a little sharp crooked knife and allowed to cool and set. Finally when cold, it was taken out and scraped and polished again and again and finally when it was all done a silversixpence was beaten and a little thistle cut from it and planted in the front of the shank of the spoon.”

Within the Highland Folk Museum collection we have three spoon moulds of the type mentioned within the story by Dugald, each of which would have produced a spoon of slightly different size and shape. Even if the same mould was used, given the nature of horn it can be certain that every spoon made is unique, and there are even accounts that within a family no one would ever dare to use another person’s spoon, each knowing their own due to the pattern within the horn.(2) Not only do all of our horn items have their own unique pattern, but many also initials either scratched or tooled in to the surface, meaning there is no mistaking who it belongs to.

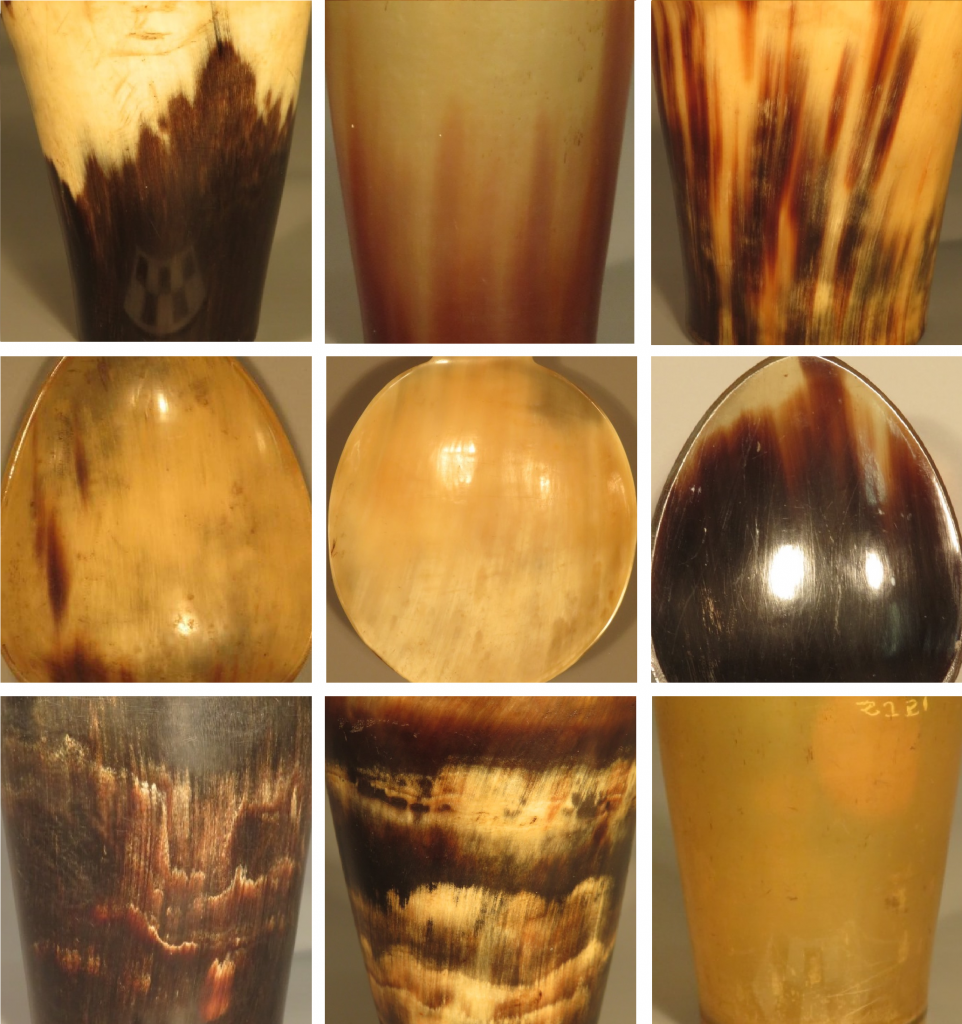

Different patterns that can be found within horn.

Above: L, SKA.0062, M, SKA.0046, R, SKA.0045

Below: SFE.0006, M, SKA.0011, R, SKA.0031

Another interesting quirk of our horn spoon collection is that some of them have been made to contain a whistle on one end. To create this a linear hollow of roughly 6cm is formed at the end of the handle, and a notch cut in that acts as an air hole. There are no holes for your fingers to play like a recorder or chanter, but Helen and I have been reliably informed by the Highland Folk Museum’s ex-curator, Ross Nobel, that these whistles were for calling horses in, as well as for entertainment. Although intrigued we’ve yet to blow in to them to see what kind of noise they make…

Above: L, SKA.0008 and R, SKA.0010

Below: L, SKA.0029 and R, SKA.0096

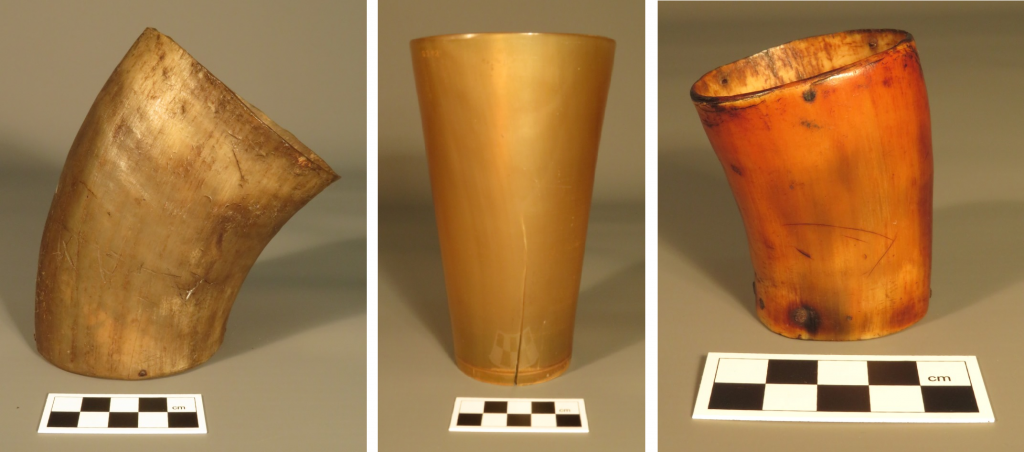

Another item that was commonly used and created using horn are tumblers, sometimes known as beakers, and within the collection we have 35 of these vessels. These would have been used as everyday drinking vessels and are thought to have been a natural development from the drinking horn which was difficult to set down or store. Unlike the spoons, where the horn first had to be flattened before the spoon shape was moulded, tumblers would have been made by forcing an un-slit, heated section of horn on to a metal or wooden former.

L, SJ.0048, M, SJ.0061, and R, SJ.0040

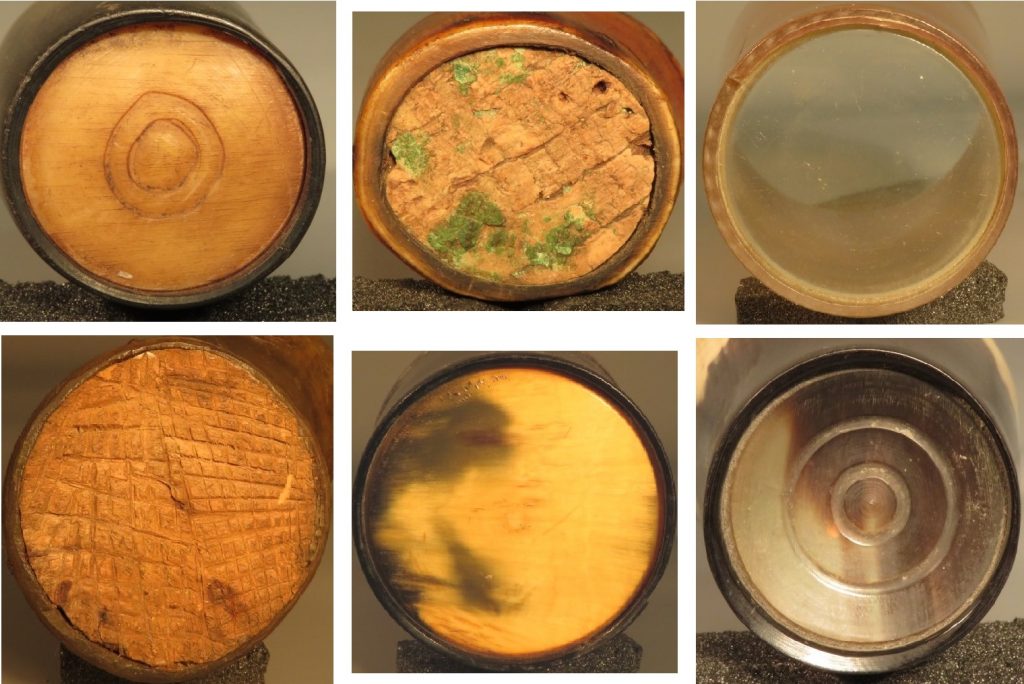

When cooled, the beaker could then be removed from the former and turned on a lathe to smooth any rough surfaces, however, we also have several in the collection where the rough surface and bent shape of the horn has been retained. To make a water-tight base for the tumblers a groove would have been formed on the inside of the narrow end of the tumbler, and this end heated until it was malleable. A circular disk of glass or horn would then have been slipped in, and the horn would cool and contract, holding the base in place. Within the collection we have several tumblers with very intricate, turned bases, as well as a few where the base has broken and been repaired using either cork or wood.

Above: L, SJ.0007, M, SJ.0040, R, SJ.0063

Below: L, SJ.0048, M, SJ.0065, R, SJ.0009

Deterioration and condition checking

When condition checking an item, such as a horn spoon or tumbler, it helps for me to know a little about the material that it is made from, as well as the manufacturing processes it has gone through, because this will often affect how an object will age and deteriorate. Within horn, due to the process of heating and moulding, it is common to see very small stress lines within spoons, often around the edges of the bowl or down the handle, which indicate areas of internal pressure, which are sometimes a precursor to more serious deterioration. Given that horn forms in layers around a bony core, it is also common to find that horn objects are beginning to delaminate, which can be seen when thin layers within the object begin to lift and separate from one another. Another very common (and often disgusting!) form of deterioration within horn is scaling, when the surface breaks out in to little scales, often which are lifting slightly from the surface and which have darkened with caught-up dust and dirt.

Deterioration of some of the spoons.

Although these types of deterioration are visually intrusive, within social history conservation we don’t usually repair this type of damage as it is seen to be an indication of the age and usage of an object, and often repair will create equally damaging new pressures. Instead of repair we will fully document these deterioration processes so that we can easily tell if, and how, it is getting worse.

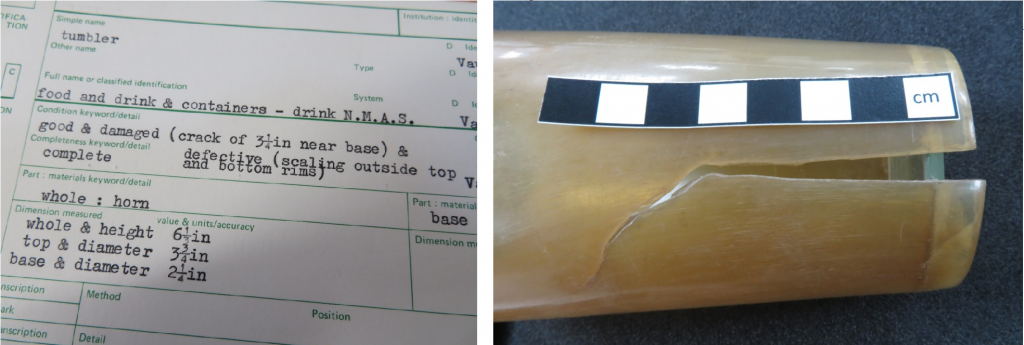

We are very lucky that during the 1980s an audit similar to the work that Helen and I are doing was undertaken on the hornware collection, and during this time any issues with condition were noted. While writing my own condition check I will read over these records, and these will allow me to make a comparison about how an object has changed over the years. For example, thanks to our records I know that SJ.0060, a horn beaker with a glass base, had a crack of 3 ¼ inches in 1980.

L, a record card for SJ.0060, R, the beaker today

Measuring the same beaker and damage today, I can see that this crack has not got any worse in almost 40 years, which is great. We can therefore assume that this damage to the beaker has been created by changes in environmental conditions, where the horn has contracted possibly due to dry air, whereas the glass base has remained the same. Now that the hornware collection is stored in our environmentally controlled store at Am Fasgadh, hopefully no more damage will be done.

Once all of the spoons and ladles have been condition checked, the next important stage in our project is to re-store them. Before we begun work the spoons were badly stored in acidic cardboard boxes, liable to hit against each other, and in no particular order. They are now stored within Correx boxes, with custom inert foam cut-outs, and in numerical order. This ensures that the objects are well supported and easy to find, as well as protected from over handling and dust and dirt. Now properly rehoused, we can continue to monitor our objects to ensure that no more damage is being done.

L, the spoons before and R, the spoons after our project.

References

(1) Grant, I.F. (2007), The Making of Am Fasgadh. Edinburgh: NMS Enterprises, p. 172

(2) Scott-Moncreiff, G (1951) Living traditions of Scotland. Edinburgh: His Majesty’s Stationery Office, p.17

Hardwick, P (1981) Discovering Horn. Cambridge: Lutterworth Press.

Rachael

Previous blog post – Marvellous Barvas Part 2