You’ll have read in several of our previous blog posts that Helen and I have become a little obsessed with baskets over the previous year, having started our project by working on them and subsequently been unable to get enough of them. Another craft related to basketry, which we’ve touched on during our research, is vernacular rope work, of which the Folk Museum has a relatively large and significant collection. A recent loan to An Lanntair, an arts venue in Stornoway on the Island of Lewis, gave us a great excuse to delve in to this area of the collection and give some love and attention to PZ.0001, a puffin snare from St. Kilda.

PZ.0001, a puffin snare from St. Kilda

St Kilda is an isolated island around 40 miles off the coast of North Uist, and although once populated, it was evacuated in the 1930s. St Kildans kept sheep and some cattle, but the rough seas around the island meant that the inhabitants generally did not fish, and instead their diet consisted largely of sea birds such as fulmars, gannets and puffins. Not only did they eat the eggs as well as the young and adult birds, but they also used the fat of the birds to make candles and the bones to make fertiliser. There were many ingenious ways used to catch a puffin, such as using fowling ropes to dangle men over cliffs, but the most intricate example of this (now illegal) activity is a puffin snare.

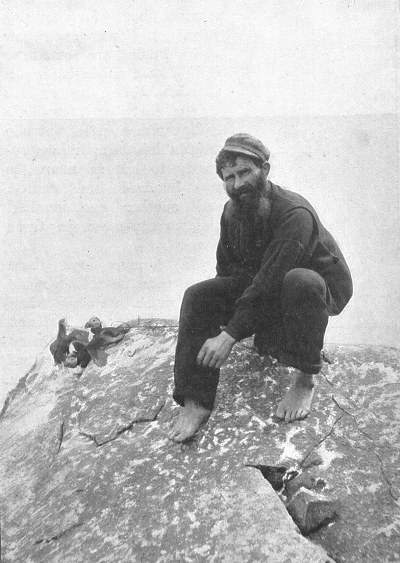

Finlay Gillies catching puffins using a snare.

Photo taken from Kearton, R (1897) With Nature and a Camera. pg. 111.

There is a great account of the people of St Kilda catching puffins within Richard Kearton’s book With Nature and Camera (1), which describes how a local would place the snare on the side of a rock known to be frequented by birds. Either end of the snare would be weighed down with a stone, and the nooses opened wide on either side of the main rope. Four puffins were caught as the author watched, two by both legs, one by a leg and neck, and the final by one leg. This was a very successful method of fowling as it is said that it was common to catch seven or eight puffins in such a snare, with one lady even snaring two hundred and eighty in only three hours.

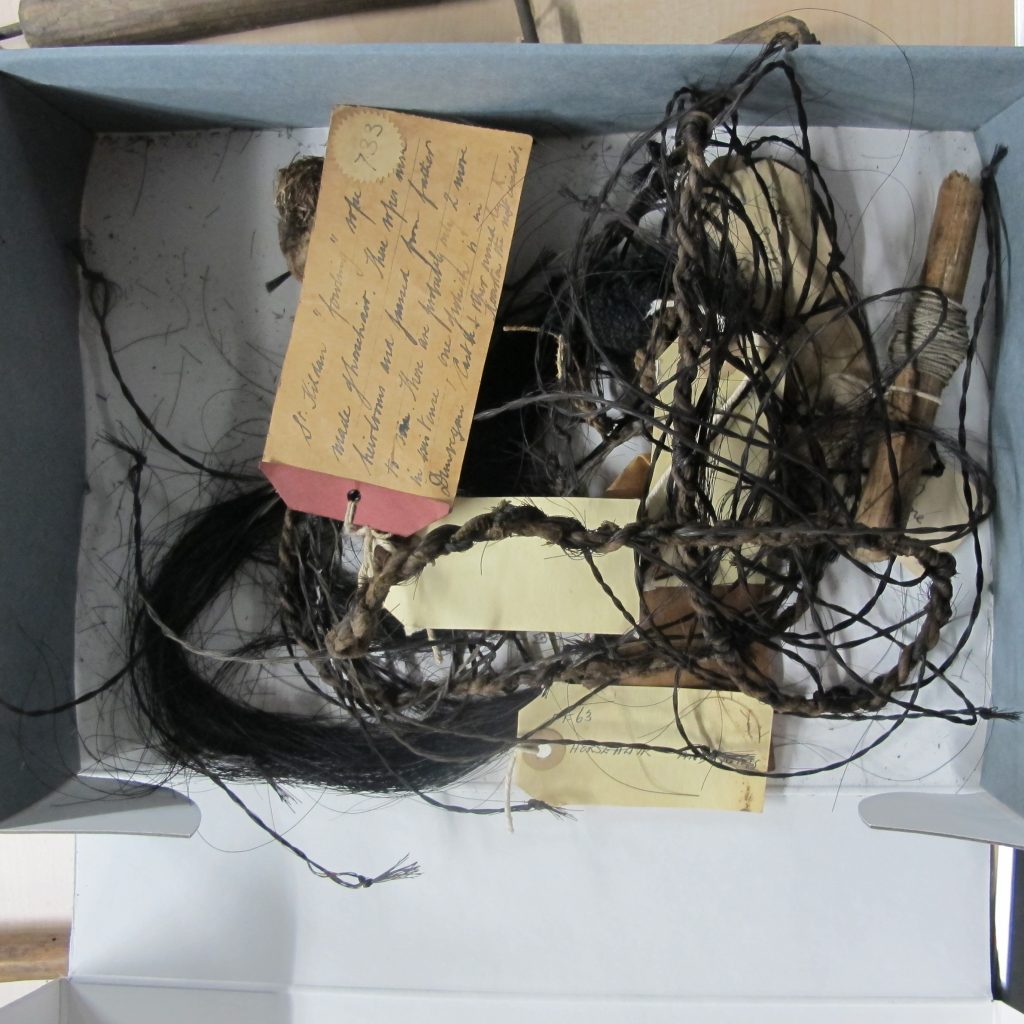

Above, the puffin snare before mounting

Below, beginning to untangle the snare

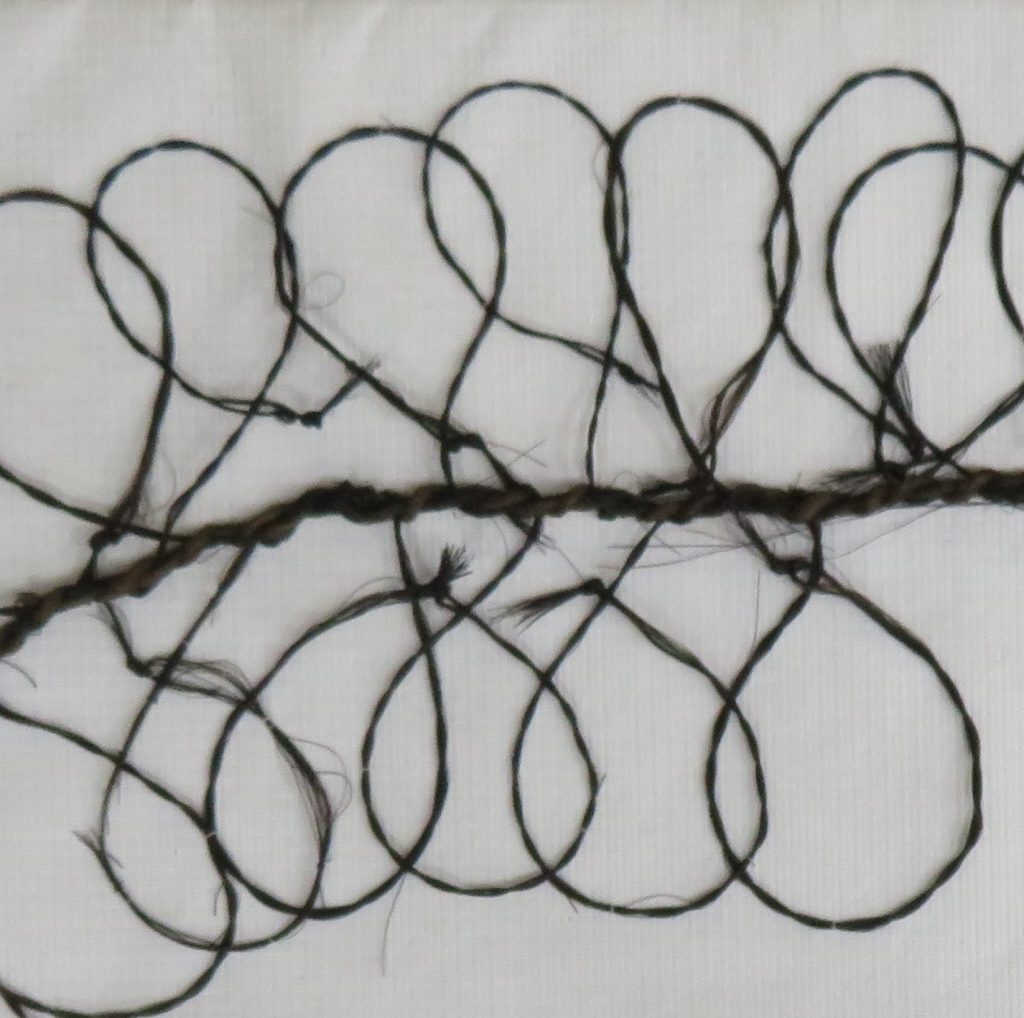

Once it was confirmed that this item was to go on loan my first job was to take it to the lab and check to make sure it was in sturdy enough condition for both travel and display. Unfortunately, when found in store the snare was all tangled up along with another length of horsehair rope, so the first job was to take it out and see exactly what we had. To do this I slowly untangled everything, and used pins to hold any unruly ropes in to position. Upon examination I found that the object consisted of a central length of two-ply plant fibre rope, within which are bound many lengths of thin two-ply horsehair rope, knotted at each end. Although these would have once formed the nooses of the snare, every length of horsehair was instead laying loose and linear, and the object appeared very confusing to anyone who looked at it, as it was uncertain how a puffin could have become entangled.

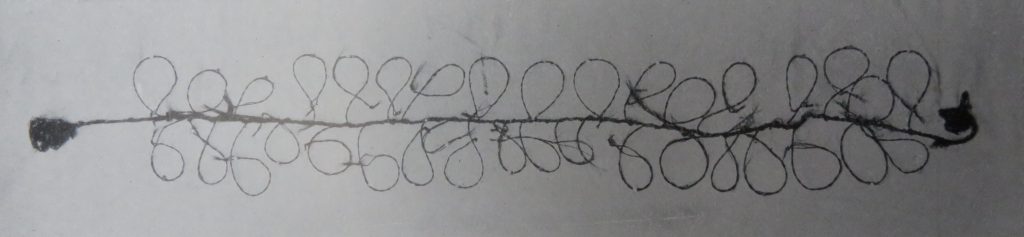

Above, a photograph of a puffin snare, taken from Kearton (1897) With Nature and a Camera, pg.112

Below, beginning to form the nooses

Luckily, although this is a very rare object and we don’t know of any others that have survived, Kearton included within his book a very clear photograph of a similar snare, and from this I was able to confirm that the lengths of horsehair would have been twisted upon themselves to form small nooses. I was able to do this with many of the ropes, but some of them were too fragile, with the knotted ends only attached by one or two strands of hair. To mend these I painted some cotton thread with acrylic paint and used it to tie the strands lightly together. This method will hold the hairs in place, and on closer inspection it is obvious that it is a modern repair which can be easily taken off if needed. Rather than twisting the damaged ends to form nooses, I pinned them in to position to make it look as though they were forming a snare shape.

Some breaks to the horsehair nooses before (left) and after (right) tying with cotton thread

Once I knew what form the snare should take it was time to start mounting it. To do this I measured out the size of the display case base on Plastazote, archival quality foam, and covered this in a layer of Tyvek, an archival quality material. I positioned the snare carefully on the board, and using cotton thread stitched each noose in to position, making sure that none of the broken horsehair was loose or sticking up. On installation day Helen and I were able to easily place the board in the case without disturbing the snare itself, ready for display. We know that I.F. Grant had this snare positioned on a wall when the museum was housed in Kingussie, but even then the horsehair was not twisted to form nooses and instead lay loose. It was a massive privilege for me to be able to mount this object, allowing it to be seen on display in its original shape for the first time since it was collected.

The snare on display at An Lanntair, for the Cuimhne/Memory exhibition

Keep an eye out for our next blog post, where Helen discusses how objects such as the snare fit into the exhibition and symposium theme of “memory”.

Rachael

More information about An Lanntair and the Cuimhne/Memory exhibition can be found on their website and on their blog.

(1) Kearton, R. (1897) With Nature and Camera. London: Cassell and Company, Limited.