On 1st August 1832 a controversial Act of Parliament received royal assent in Great Britain and Ireland. Going by the long title ‘An Act for regulating Schools of Anatomy’ the act marked a key stage in the long story of anatomy and human dissection. To mark the 190th anniversary of this Act, and International Women’s Day, our Community Engagement Officer, Lorna Steele-McGinn, met world-renowned Forensic Anthropologist Professor Dame Sue Black to learn more. (Click on link for film)

Dissecting the 1832 Anatomy Act: In conversation with Professor Dame Sue Black

To accompany the interview we have produced this blog, giving a brief history of the study of anatomy in the United Kingdom and providing viewers a chance to study the documents discussed in a little more depth (every image can be enlarged by clicking on it).

To understand the importance of the 1832 Anatomy Act, and the controversy surrounding it, it is necessary to go further back in time and put it into context. For centuries there has been an element of conflict between the necessary desire for scientific and medical progress and the, perhaps natural, aversion to the use of bodies for the purpose of that advancement.

Generations of our predecessors believed that for a person to be resurrected after death (a key part of many world religions) there was a requirement for their body to be intact at burial.

The process of dissection therefore was often thought of as abhorrent and those who sought to practise anatomical study had very few specimens on which to work. In addition to this, for many years, there was little or no process for preserving the bodies, meaning that any work had to be undertaken in less-than-ideal conditions.

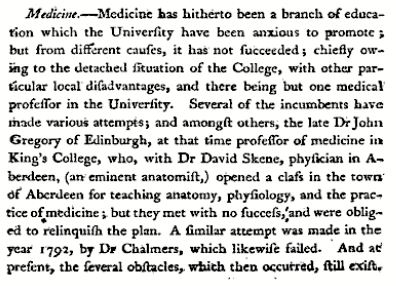

In 1505 a charter was awarded to the Barbers and Surgeons in Edinburgh, uniting them as an Incorporation and authorising them to have one body a year for dissection – that of a convicted criminal. Thus started a long connection between the city of Edinburgh and the study of anatomy, which is still ongoing today (further information on this can be found by visiting https://www.rcsed.ac.uk/the-college/about-us/history-and-vision). By the late 1600s, as the number studying medicine increased, there were pleas for access to additional corpses and some of these requests were granted, such as that of Alexander Monteith, Deacon of the Incorporation. Monteith negotiated with Edinburgh Town Council for access to bodies that died in prison on the understanding that the Incorporation would in return build an anatomy theatre for public dissections – the creation of Surgeon’s Hall. Over the subsequent years a number of other anatomy schools and dissecting theatres were established in the country.

The next big moment in the story of the study of anatomy in Scotland comes with the passing, in 1752, of what is commonly known as the Murder Act: ‘An Act for better preventing the horrid crime of murder’.

The Act stipulated that those convicted of murder should not only be hanged but that after death, “some further terror and peculiar mark of infamy be added to the punishment”. This was to be in the form of either hanging in chains or public dissection. The aim being that “in no case whatsoever shall the body of any murderer be suffered to be buried.”

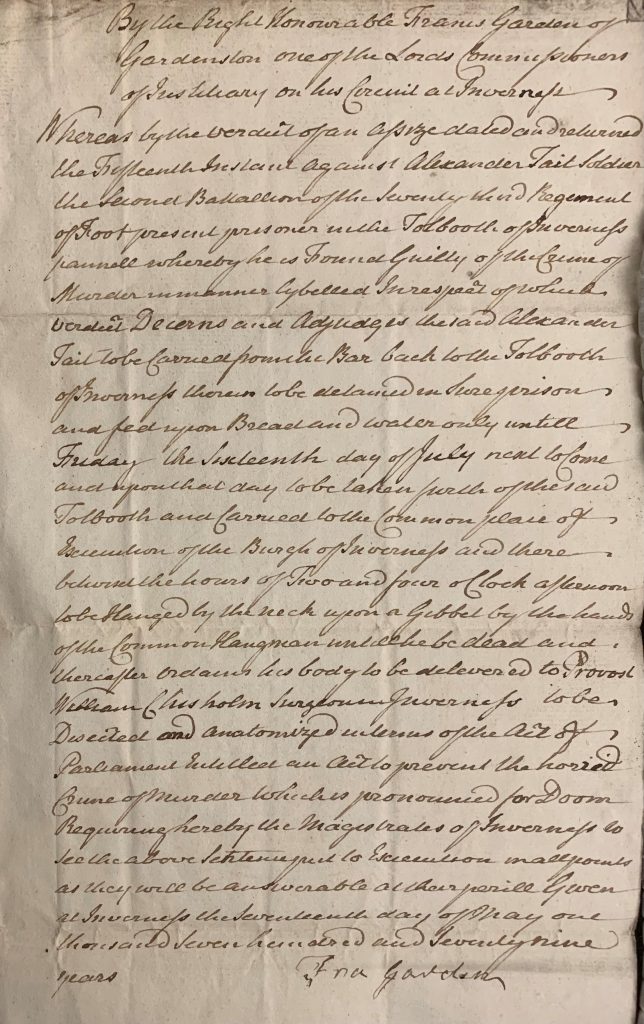

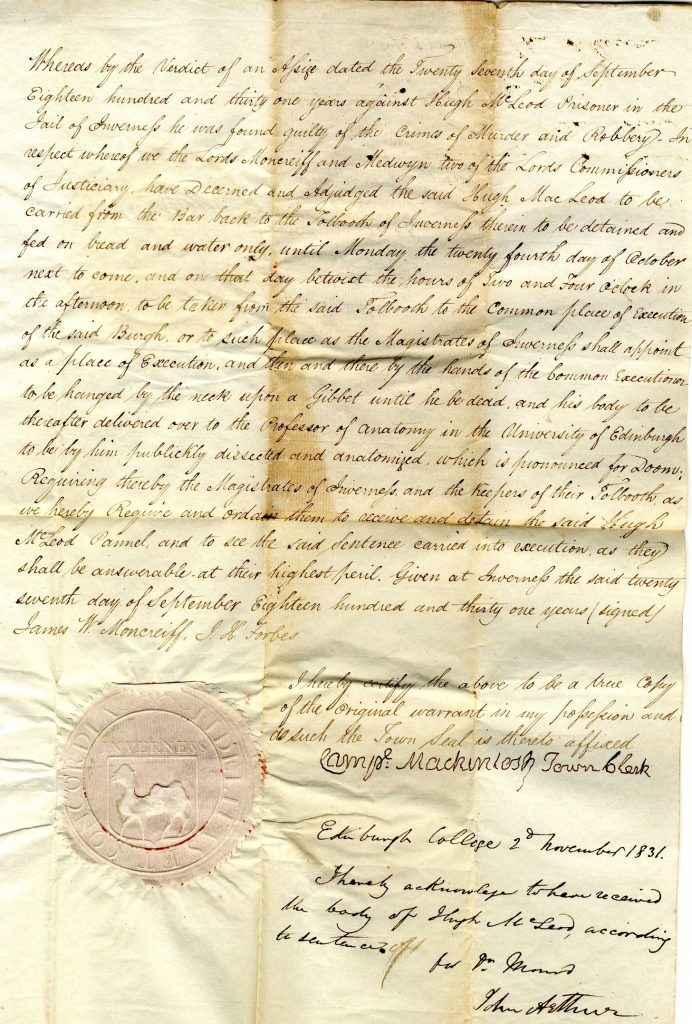

The Highland Archive Centre holds among its collections a wide range of court process papers, and among those of the High Court can be found examples both of convicted murderers being sentenced to hanging in chains and being sent for public dissection. Thus the work of the anatomists came to be even more associated with those of criminal tendencies – to be dissected was to be further punished and humiliated. The examples below are just two of these. The story of Hugh McLeod, the Assynt Murderer, whose Dead Warrant can be seen below, can be found here.

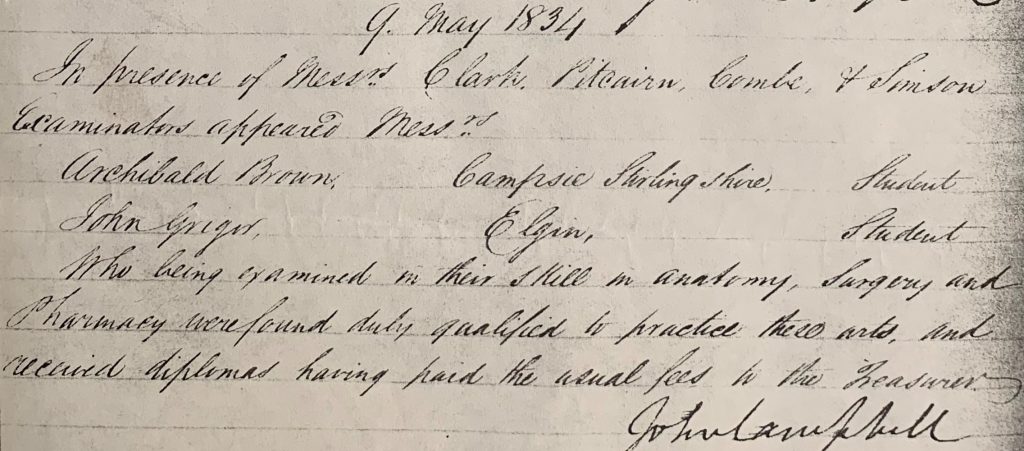

Dead warrant of Alexander Tait, soldier, convicted of murder and sentenced to hanging and dissection, 1779 (GB0232/L/INV/HC/12/16)

Dead warrant for Hugh McLeod, the Assynt murderer, convicted of murder and sentenced to be hanged and his body sent to Edinburgh for dissection (with receipt), 1831 (GB0232/L/INV/HC/12/29)

This change of legislation no doubt increased the supply of bodies but the late 18th/early 19th century was a boom time for scientific knowledge and as the number of anatomy schools and students increased so too did the demand for specimens from which the students could learn – the silent teachers.

It was at this moment of intense supply/demand issues that the infamous ‘bodysnatchers’ or ‘resurrection men’ started to appear. Men who would, under cover of darkness, enter graveyards to ‘resurrect’ those who had been recently buried and sell the corpses on to the anatomy schools. Or in the case of those most famous of bodysnatchers, Burke & Hare in Edinburgh, go as far as murdering people rather than waiting for them to die.

A wave of fear spread through the country, with both individuals and communities purchasing mort safes (a heavy iron cage to place over a grave) and a variety of methods devised to prevent bodies being exhumed and removed. Several Highland graveyards still contain watch houses (built for members of the community to sit in following a burial until the corpse was too decomposed to be of use to the anatomists). There is an example of a mort house in Boleskine graveyard (a secure building constructed to house dead bodies until they were no longer useable when they would be buried – around six weeks).

Ardersier Watch House. www.ambaile.org.uk

Petty Watch House www.ambaile.org.uk

Dunlichity Watch House www.ambaile.org.uk

Boleskine Mort House www.ambaile.org.uk

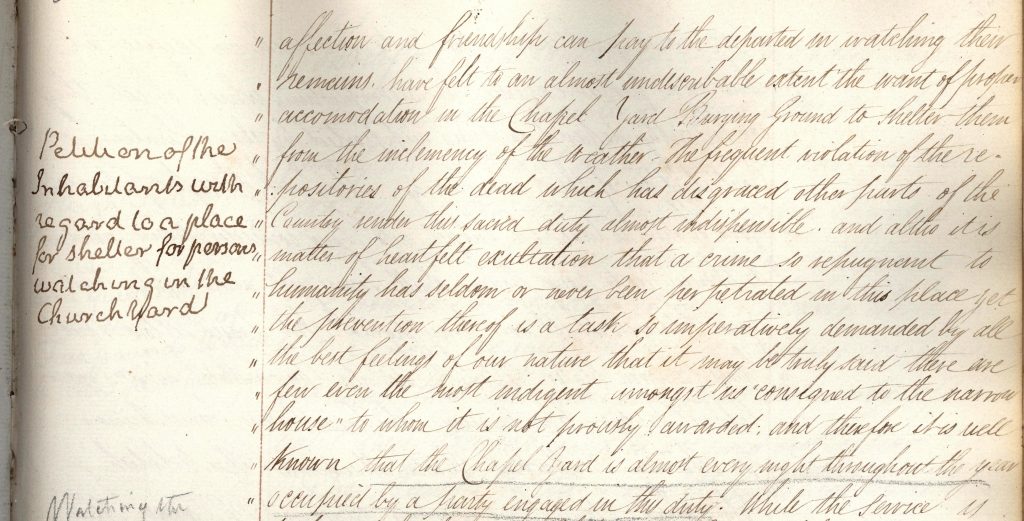

As far as we are aware no bodies were snatched in the Highlands for the purposes of dissection but the extent of the concern is visible in documents such as the 1827 Inverness Town Council minutes, which contain a petition by the inhabitants of Inverness to build a small structure with a fireplace in the Chapel Yard to afford better shelter and protection for those “watching the dead”. It reports that “the frequent violation of the repositories of the dead which has disgraced other parts of the country render this sacred duty almost indispensable and although it is a matter of heartfelt exultation that a crime so repugnant to humanity has seldom or never been perpetrated in this place yet the prevention thereof is a task so imperatively demanded by all the best feeling of our nature…and it is well known that the Chapel Yard is almost every night throughout the year occupied by a party engaged in this duty.”

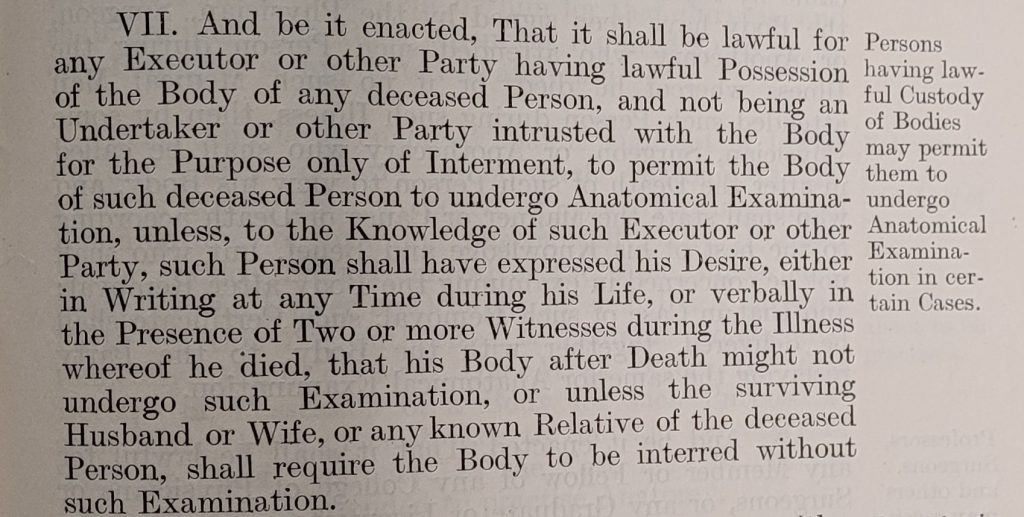

The constant publicity and fear surrounding this issue was certainly a contributing factor to the Anatomy Act being passed in 1832 – if the anatomists had a better supply of bodies there would be no market for bodies to be resurrected and sold. However the proposed Act was controversial and took time to gather support. There was a general distrust of anatomists and the proposal the Act made to give them access to any unclaimed bodies (i.e. those in prisons or poorhouses) effectively moved the “punishment” of dissection from convicted murderers to those whose only crime was to be poor.

Despite this, after several years, the bill did indeed gather sufficient support to be passed by both the House of Commons and the House of Lords, going on to receive royal assent and pass into law on 1st August 1832.

In addition to Section VII, which allowed for the use of unclaimed bodies, the Act also regulated the work of anatomists – requiring that anyone who practised obtain a licence to do so – and established four ‘Inspectors of Anatomy’ who would have oversight of the system.

Although public discomfort about the provisions of the Act continued (particularly the feeling that it reinforced a two-tier society with the poor as the subjects and the elite as the beneficiaries), there is little doubt that it succeeded in its aims of a) reducing the market for resurrected bodies and b) advancing medical science.

Throughout the 19th century medical advances flourished and anatomists (and therefore surgeons) were able to make leaps in their knowledge of the workings of the human body. This was aided by related developments such as the discovery of more effective preservatives including formaldehyde, which enabled students to spend more time examining and learning from their subjects. The improvement in preservation techniques also provided anatomical artists with more time to create medical illustrations for teaching purposes and it was at this time that textbooks (including the famous Gray’s Anatomy of 1858) appeared. In their turn, they became tools that would inform generations of anatomists up to the present day, who still use them alongside donated bodies.

‘Illustrations of Dissections in a series of original coloured plates the size of life representing the Dissection of the Human Body’, by George Viner Ellis and G H Ford, Esq, 1867 (GB0232/HHB/1/16/1)

There remains an awkwardness for many people around the subject of anatomy and human dissection – the work of Burke and Hare and the resurrection men has cast long shadows, in addition to a natural uneasiness with the idea of our bodies, or those of our loved ones, being cut open.

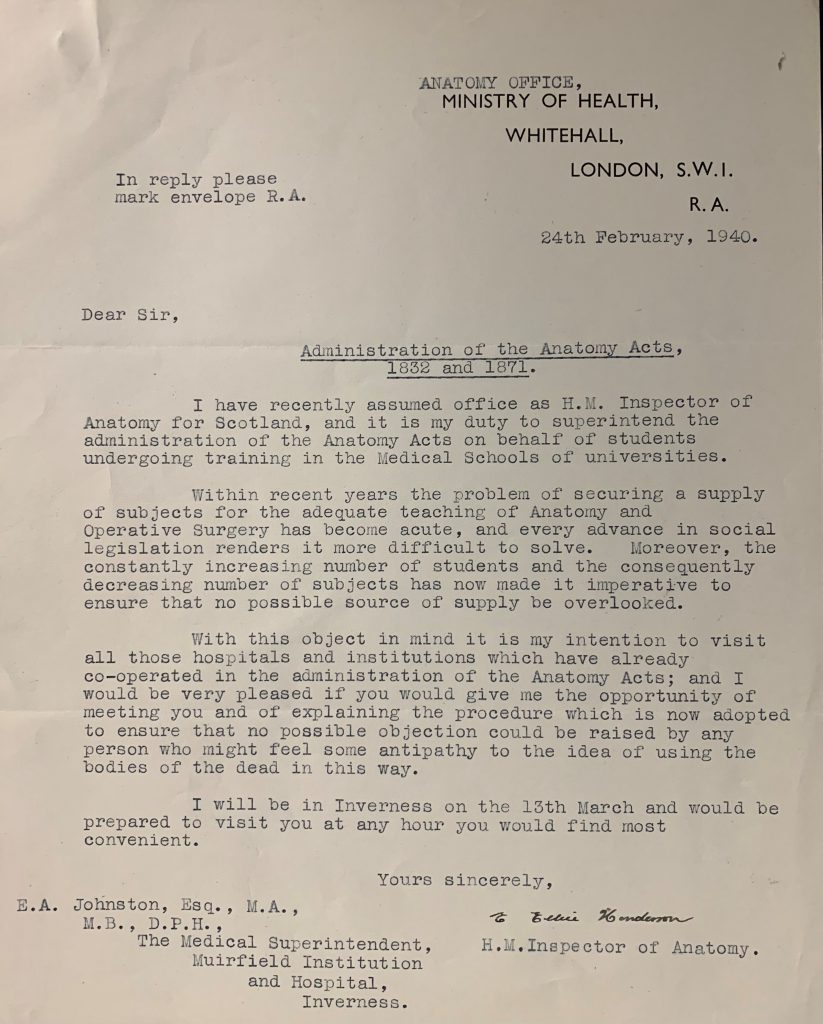

There have continued to be times of critical shortage of bodies for students to learn from as a 1940 letter from the Inspector of Anatomy to the Muirfield Institution and Hospital illustrates.

However, the work of anatomists and their sister professionals (pathologists, forensic anthropologists and others) down the centuries has informed our knowledge of medical science, has secured the conviction of criminals, has proved the innocence of the wrongly accused and has changed the way we understand and treat a myriad of illnesses and conditions. Much of the medical knowledge we rely on today is thanks to them and to those whose bodies found, and find, their way into their hands.

With thanks to Professor Dame Sue Black for sharing her knowledge and to NHS Highland for allowing us to publish some of the many documents we care for on their behalf.